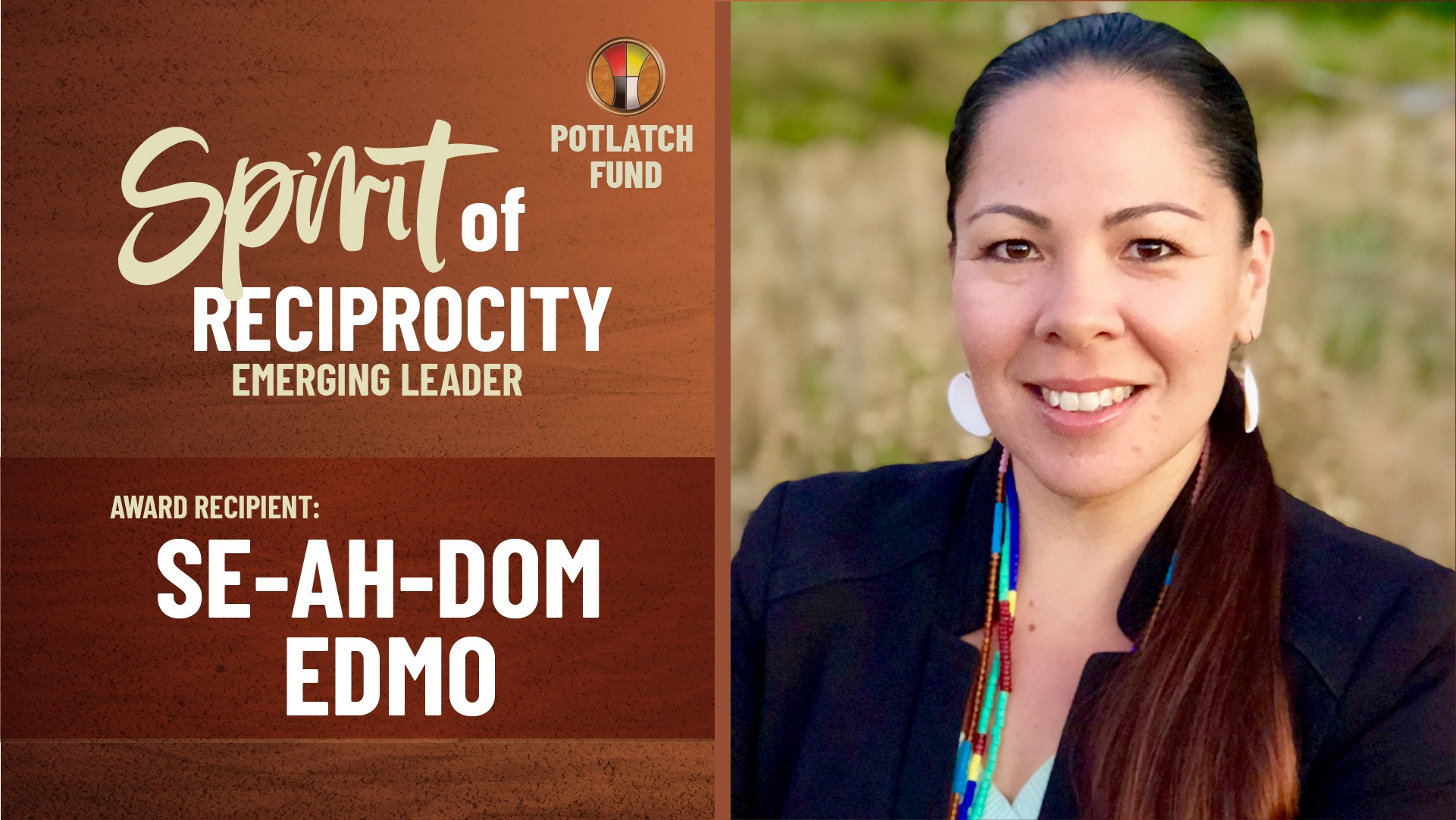

SE-AH-DOM EDMO

2020 SPIRIT OF RECIPROCITY

Award Recipient

The Spirit of Reciprocity Award was established by Potlatch Fund to recognize emerging leaders from the local community who have demonstrated significant promise of leadership, participation, and accomplishment within Northwest Indian Country.

This year’s winner of the award is Se-ah-dom Edmo of Portland, Oregon. Se-ah-dom (Shoshone-Bannock, Nez Perce and Yakama) is currently the executive director of MRG Foundation and a founder of the Northwest Justice Funders Collective, a group of eight foundations including Potlatch Fund that intentionally fund communities of color, LGBTQ+ people, women, immigrants, and refugees, and grassroots groups working for justice.

Se-ah-dom comes from a background of advocacy and organizing work on behalf of tribes and LBGTQ justice. She is the co-editor of the Tribal Equity Toolkit 3.0: Tribal Resolutions and Codes for Two Spirit and LGBT Justice in Indian Country and American Indian Identity: Citizenship, Membership & Blood. Prior to joining the MRG Foundation, she was the coalition convener for Senate Bill 13 in Oregon, which established and funded teaching of Indian history and sovereignty in K-12 schools across the state.

In all that she does, Se-ah-dom is focused on upending and transforming the current model of philanthropy to achieve social, racial, economic, and environmental justice for both Native communities and others excluded by its current practices.

Se-ah-dom lives in Portland with her husband, James, and their children Siale, Imasees, and Miyosiwin, as well as her parents, Ed and Carol Edmo.

DISRUPTING STATUS-QUO PHILANTHROPY

A CONVERSATION WITH

Se-ah-dom Edmo

Se-ah-dom Edmo is an anomaly. As a Native woman running a non-Native foundation, she is part of a very small club. In fact, you’d be hard-pressed to call it a club at all.

“According to the Council on Foundations, individuals with Native American or Alaska Native heritage consist of .06 percent of executive positions,” she says. “While that data point is frustratingly low, it really lacks the nuance of the number of Indigenous women running non-Native or mainstream foundations. So in the Northwest, I think I’m one of two. And I, quite frankly, don’t know of any others in the United States.”

The foundation where Se-ah-dom serves as executive director— MRG Foundation in Oregon—is, as she describes it, “a thought leader in challenging ideas of wealth, power, and what it means to succeed in this political, social, and economic ecosystem in the Northwest.

“We fund social, racial, economic and environmental justice,” she says, “and that’s all we’ve funded since we were founded in 1976.”

Because she came to MRG two years ago from a background in organizing and advocacy work, it’s proved a good fit for her combination of abilities and also her determination to disrupt and transform the current model of philanthropy. Among other things, that will require changing how we talk about mainstream foundations and philanthropy.

“I prefer using the term ‘status-quo philanthropy’ over mainstream or traditional philanthropy, although I don’t know that it completely captures the nature of what has happened and is happening in the field. I feel like when we call them mainstream or traditional philanthropy, it normalizes their practices in a way that they should absolutely never be normalized,” she says.

One result of this semantic shift is a reconsideration of what defines radical philanthropy, a label that has long been applied to grassroots organizations and funders like MRG.

“Being about social justice may seem radical,” Se-ah-dom says. “But to me the kind of philanthropy that we practice is practical. It’s logical. It’s grounded in building social, economic, and political power for our communities so that we don’t keep getting the same results we’re getting in terms of oppressive practices and policies that disparately impact our communities.

Potlatch Fund and the community comes together virtually for a night of Indigenous Resilience; Colonial Resistance at the 2020 Potlatch Fund Annual Gala on Saturday, November 7, at 5:00 pm PST.

REGISTER TODAY FOR THIS FREE VIRTUAL EVENT.

(Sign up early to be entered into the Early Registration Raffle)

There is no cost to register.

“Status-quo philanthropy is radical,” she continues, “like to go to the—and I’m going to say a word here and I challenge you to find a different one—literal lengths of legal and narrative f**kery that you have to jump to in your head to justify the consolidation of wealth and power into the hands of a few is exactly what status quo philanthropy is and does, and that is radical. Status-quo philanthropy practices charity—giving dollars and not investing in change—and that’s actually animating and exacerbating the white nationalist and white supremacist cultures that are rising right now. Philanthropy, as a sector, is complicit.”

At MRG, Se-ah-dom and her colleagues are disrupting status-quo philanthropy by addressing one of philanthropy’s holy grails: donor-advised funds. “Many, many community foundations across the nation describe them as people’s philanthropic checkbooks, which I hate,” Se-ah-dom says. “They’re ways of giving people credit for giving money away, and they never actually cede control over that money to the communities they’re intended to benefit.”

Instead, at MRG they are preparing to launch what they’re calling “Donor in Movement” Funds to not only shift money to the front lines of movements but also to shift power regarding who is at the table making decisions about where money is invested and how to invest it. The funds are one way to operationalize a new model of philanthropy, and MRG intends to make the donor contract public for other philanthropic institutions to use with their wealthy donors.

When the COVID-19 crisis hit, MRG chose once again to upend philanthropy’s usual practices. Because of their relatively small size, “we knew we weren’t going to be the most impactful foundation out there,” according to Se-ah-dom. “We knew we couldn’t move the dollars that status-quo philanthropy could, but we could root our response in racial and economic justice in a way that worked. And by going public we would ground the narrative in a way that all other philanthropic entities would have to respond to, they would have to differentiate themselves from. So that’s what we chose to do.”

They made the decision early in the pandemic to liquidate 30 percent of their operating reserves. “And we did it fast and first because we wanted to set the narrative shift to reflect what we wanted to see in philanthropy,” she says.

MRG quickly grew its COVID fund—from $300,000 to $3 million in six weeks—and distributed those funds to groups on the front lines in the same time frame. The amount represented more than they had awarded in the last five years combined and 14 percent of MRG’s total grants ever given in their 44 years of operation.

“It was an intense time,” says Se-ah-dom, “and I also think it helped ground us in that we wanted to be that much more community-driven and community-led.”

In the midst of their COVID response, MRG made its largest-ever grant to support the Oregon Worker Relief Fund, which has grown to be one of the nation’s largest mass mutual aid programs, to support the immigrant and refugee community in Oregon. Undocumented families were left out of CARES Act funding, and because of this initial investment by MRG, the fund was able to leverage an additional $30 million from the State of Oregon for undocumented workers who lost jobs or who were forced to quarantine because of their status as essential workers or who were facing other hardships because of the pandemic.

The Northwest Justice Funders Collective was another result of the crisis brought on by the pandemic. Composed of eight regional foundations, the collective is moving money to organizations on the front lines in communities impacted by COVID because, Se-ah-dom says, “we all engage within the communities we serve through kinship, understanding that kinship and our relationships, our interconnectedness, are vital to the work that we do.”

While COVID-19 has highlighted the many ways Indigenous and other organizations led by people of color are disproportionately affected by both the pandemic and status quo philanthropy’s consolidation of power, it also has the potential to drive change, but “only if we let it,” according to Se-ah-dom. “And only if we choose to create those pathways.”

Recently, Se-ah-dom was asked in an interview what she would want 2020 to be remembered for, and her answer summarizes much of what she believes needs to change in philanthropy for consistently under-resourced communities to thrive into the future.

“I think 2020 is the year that philanthropy realizes that we have been created to be in service to the movement for justice,” she says. “It’s the year we begin to operationalize that in such bold ways that it begins to make up for the years of starving communities of wealth and the ability to build wealth, and even just to survive.

“For so long we’ve been giving grants to communities at the level of what we think they deserve, rather than what they need,” she continues. “And I think this community-driven, need-based philanthropy ought to be what guides us into the future.”

Potlatch Fund and the community comes together virtually for a night of Indigenous Resilience; Colonial Resistance at the 2020 Potlatch Fund Annual Gala on Saturday, November 7, at 5:00 pm PST.

REGISTER TODAY FOR THIS FREE VIRTUAL EVENT.

(Sign up early to be entered into the Early Registration Raffle)

There is no cost to register.